Woodstock 1969 is often remembered as a symbol of peace, love, and unity—a defining moment for the counterculture movement of the 1960s.

Woodstock 1969 is often remembered as a symbol of peace, love, and unity—a defining moment for the counterculture movement of the 1960s.

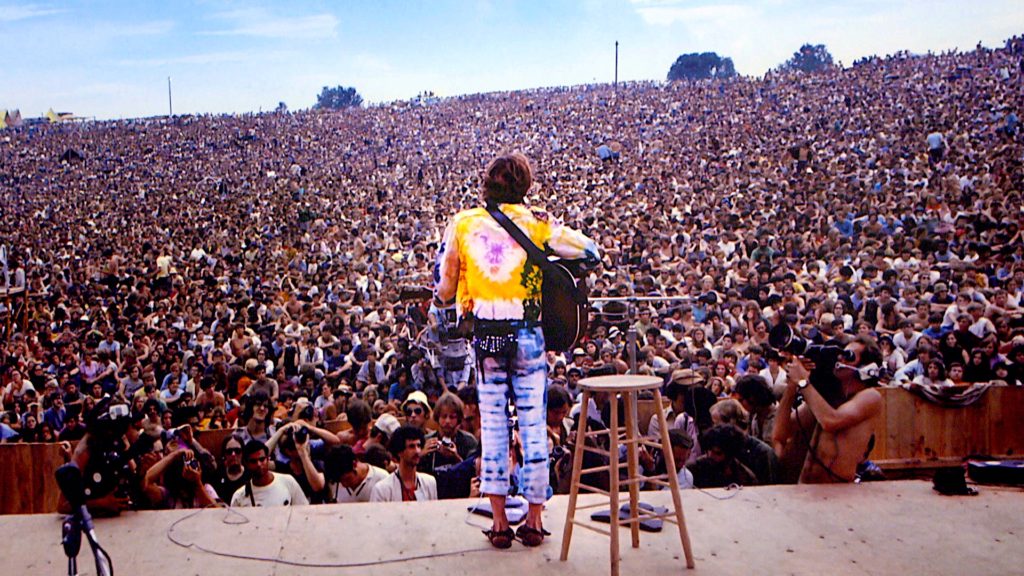

However, behind the utopian imagery lies a darker side that exposed the limits of the movement. While the festival brought together over 400,000 people to celebrate music and ideals of freedom, it also revealed cracks in the idealistic vision of a harmonious society.

The festival, held in Bethel, New York, was initially planned to host around 50,000 attendees, but when hundreds of thousands more descended on the small rural town, the infrastructure quickly collapsed. The result was chaos: food and water shortages, unsanitary conditions, and inadequate medical care for the vast crowd. While many viewed the event as a triumph of communal spirit, the logistical failure pointed to the naivety of the movement’s belief that peace and love alone could overcome practical challenges.

One of the most significant issues was the rampant drug use, which became emblematic of the counterculture. While some saw it as a form of liberation and rebellion against societal norms, the reality on the ground was much more troubling. Drug overdoses were common, and at least two deaths were recorded during the festival—one from a heroin overdose and another from a tractor accident in the chaotic conditions. Medical personnel were overwhelmed, and the lack of planning for health emergencies showed the downside of a “free-spirited” approach.

Woodstock also highlighted the fragile line between idealism and the harsh realities of human behavior. The counterculture movement prided itself on rejecting the materialism and greed of mainstream society, yet the festival’s organizers faced significant financial strain, ultimately resulting in enormous debts. Despite the focus on peace, tensions ran high at times due to the overcrowded and increasingly uncomfortable conditions. The dream of a perfectly harmonious society began to unravel as the logistical problems grew more apparent.

Moreover, the festival’s idealized image of unity masked the deeper divisions within the counterculture. While the event is often celebrated for its diversity of music and attendees, it also exposed the limits of inclusion. Many African American and other minority artists and activists felt sidelined by the largely white, middle-class audience and organizers. Woodstock may have been a celebration of anti-establishment values, but it also reflected the movement’s failure to fully address issues of race and inequality.

In the end, while Woodstock remains an iconic symbol of the 1960s, its darker side exposed the limitations of the counterculture’s vision for a new world. The festival, though a historic gathering, demonstrated that ideals alone were not enough to overcome the challenges of human nature and society’s complex realit